Murder Is Easy: Hunting for Sauron is Killer

Some unexpected parallels between the most recent Agatha Christie adaptation and Tolkien's themes

Author’s note: the following essay was first released by me a couple of weeks ago via Substack Notes and my Facebook page. But I just realized recently that it might not be accessible to those of you, my dear email subscribers, who don’t also follow me on Notes and other social media platforms. In addition, I did promise in my first blog post of 2024 that I would provide at a minimum two full essays per month, and this note is already REALLY long; a few tweaks, some quotes, and I should be able to kill two birds with one stone. So if you’ve already seen this, have fun for the second time; and if you’re seeing this for the first time, I hope you like it 😊 Credit to my friend Michael Liem for coming up with the joke that makes up the title.

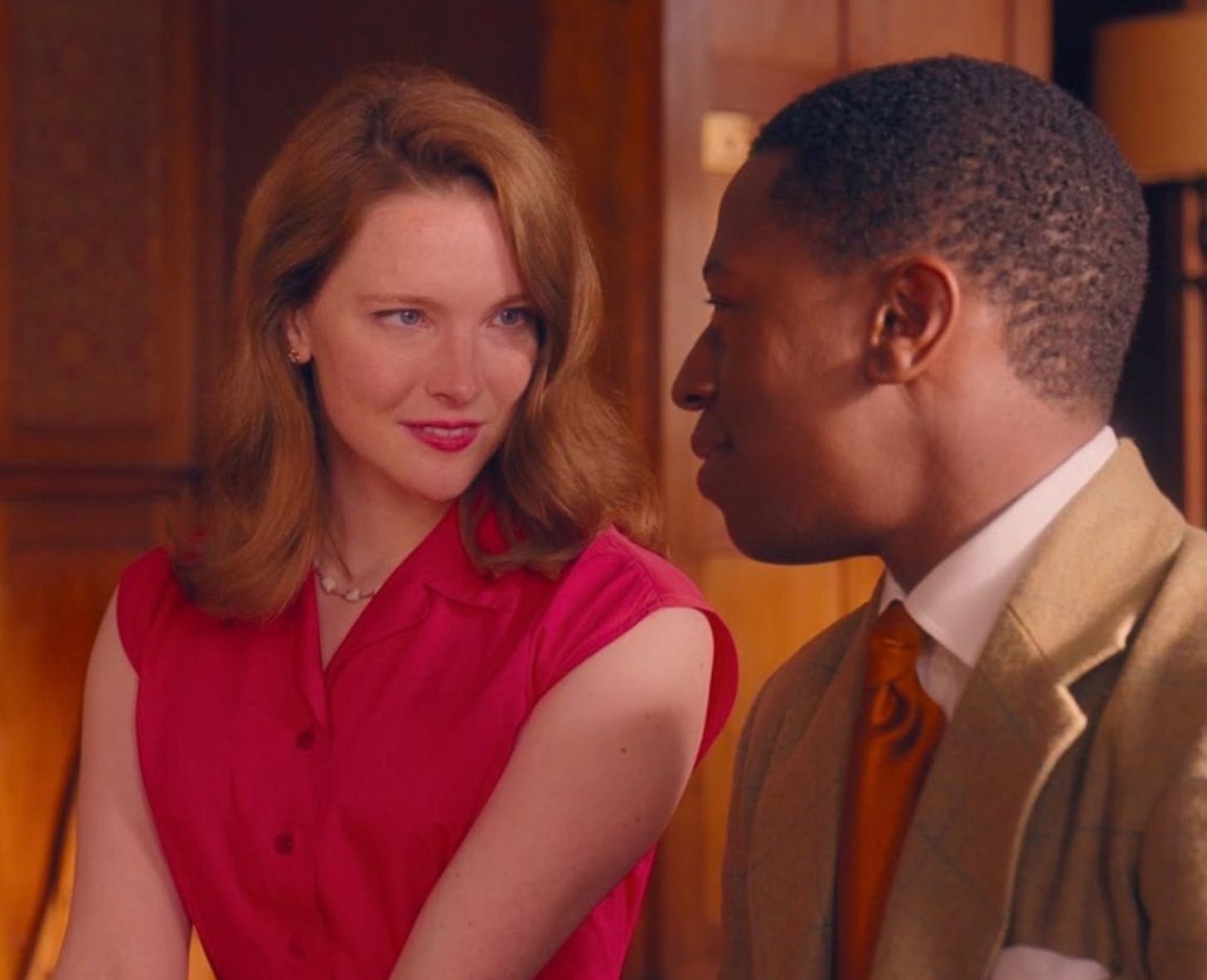

“Murder is easy for a particular sort of person.” So says Penelope Wilton’s Lavinia Pinkerton while on the train to London to try and report what she firmly believes is a series of murders that are ravaging her small community of Wynchewood-under-Ashe. Sadly, within just a few hours she herself ends up dead, thus proving with her life that her suspicions are valid. But luckily she wasn’t just talking to herself when she said this, but to a dapper newcomer to Britain, the British-educated Nigerian Luke Obiako Fitzwilliam (David Jonsson). Given that she dies practically under his nose, Luke feels responsible for continuing her quest for justice, so off her goes to the small community to see what he can find. At first he his all alone in his quest, but being a black man in a small English community all eyes are on him. One pair of these is owned by the dainty, charming, beautiful and perceptive Bridget Conway (Morfydd Clark), who soon realizes that Luke is a man of honor and that his quest is valid; soon the two of them are hard at work together as a team of equals, to solve the murder mystery and bring peace to the community.

Given my fondness for Morfydd Clark and for her interpretation of the Galadriel of Unfinished Tales and Tolkien’s letters that we meet in Rings of Power, as soon as I learned that she would be starring in this adaptation, I was happy and excited that “Middle-earth and Wales’ sweetheart” was going to be in a project worthy of her talents. For myself and many other Morfydd fans, this provides a strong counter to claims by her haters and detractors that she is a terrible, emotionless and wooden actress; if that were true, then why is she landing such prestigious work? About a week ago, I finally had the chance to see the finished product thanks to the British Television Network on Youtube, and it did not disappoint. It was fun, enjoyable, well-done, and engrossing. And the main reason I was even interested in this production, Morfydd Clark as Bridget Conway, was a true joy; she is a ray of sunshine and a highly competent actress with great range.

But this is not a review of the adaptation as such; that would be beyond the scope of this publication. I’m not a professional film student or an Agatha Christie fan, rather I am a fan of Tolkien and Morfydd Clark. But as longtime followers may have noticed, I have a penchant for being able to draw parallels between Tolkien and various historical figures and events that might not be observable to other people who don’t have my historical training. And sometimes this spills over to other disciplines. Such was the case here, where I was able to pick up on some elements that were common between this adaptation of Christie’s novel and Tolkien’s values and ideals. They may not have been intentional on the part of the writers, but they were welcome to me.

--When we first meet Bridget, she's engaged to a rich and somewhat silly local aristocrat, Lord Gordon Whitfield (Tom Riley), who worked hard to gain his wealth and prestige and then promptly forgot about his local roots and community. Instead of giving back to the community, either his decidedly middle-class peers by birth or his new found peers by wealth, he seems to have a greater interest in living a fairly easy and aristocratic life. He even locks horns with members of his new community of Wychford-under-Ashe over his desire to build a new town: bigger, better, more modern, and bearing his name. That last point seems to be the most important element of Lord Whitfield’s enthusiasm for this new project, how to secure his own legacy and importance, never mind the damage it may do to the local community. This theme comes up frequently in Tolkien’s writings. Saruman the White, turned to jealousy and a lust for power by his study of Sauron and the Rings of Power, betrays his mission and sets out to create in Isengard a center of empire and a challenge to the Dark Tower of Barad-Dur; Lotho Sackville-Baggins, selfish and greedy, proves susceptible to the lure of unchecked industry, buys up all the best land of the Shire, and basically turns this fair country into a for-profit slum; and one need only read Tolkien’s letters to learn how any industrialist who despoiled Tolkien's beloved English countryside, born of his happy childhood in Sarehole, and thus incurred his ire.

--Bridget thankfully is a good person, despite her intended's flaws; although past heartbreak has made her somewhat jaded on the idea of true love and trust. She’s not selfish or materialistic, but all-too conscious of the need to protect herself in 1954 Britain, and so for her a marriage to Lord Whitfield will provide her safety. But she is not housebound shrinking violet. She has a car (indeed, she’s one of only a very few women in the community who can drive) and some measure of status, which she uses to roam the countryside and find a small measure of peace. She loves the free air, the woods, the open fields, and making the rounds of them. This love of and ability to find joy in the natural world is a very Tolkien-esque sentiment, one found in his own life where the places he loved the most to live were the unspoiled country thanks to his fond memories of Sarehole. The hobbits with their love of simple country life and of no machines more complicated than a hand-loom, in the Silvan Elves and Sindar whose civilizations revolve around a harmonious coexistence with the forests where they live, and the angelic Vala Yavanna, mother and protector of all growing things and those who care for them and Galadriel’s tutor during the bliss of Valinor...all of them would have approved of Bridget finding peace outdoors in the free air, as would Tolkien himself

--This is a murder mystery after all, and at one point during their investigation, running into serious obstacles from the local establishment, Bridget's new friend Luke laments "It takes power to destroy power, Bridget, and we haven't got any." Perhaps; as mentioned, Luke is Nigerian in 1954 Britain, and Bridget is only a secretary. At one point Luke is even fingered as a troublemaker and confined to his quarters by detectives from Scotland Yard, at least until local army veteran and respected community pillar Major Horton (Douglas Henshall) intercedes on his behalf. Yet, as Tolkien said in his famous letter to Milton Waldman, “...the great policies of world history, the ‘wheels of the world’, are often turned not by the lords and governors, even gods, but by the seemingly unknown and weak—owing to the secret life of creation, and the part unknowable to all wisdom but One, that resides in the intrusions of the children of God into the Drama.” And thus it is here; where the local powers fail to solve the mystery, and when the detectives from London go in a very wrong direction, it's up to a Nigerian expat and a dainty little secretary to change the course of local history.

--Some of the discourse on British social media centered on how this adaptation is "woke" and contains a "lecture on the evils of British imperialism." As is the case with most of these sorts of criticisms, I found this to be completely overblown; hardly the first time, I still encounter people saying Rings of Power and Morfydd's Galadriel are woke and destructive of Tolkien's legacy, and it never gets any less silly. So what if Fitzwilliam has been reimagined as a Nigerian, somewhat out of place in a small English town in the twilight of the British Empire, and torn between making a difference in London or back in Nigeria? That doesn't seem much more of a departure than say Kenneth Branagh making Poirot some sort of action hero. And honestly, Luke's situation reminds me a bit of Sydney Poitier's black detective Virgil Tibbs in the classic 1967 "In the Heat of the Night"; not quite as excellent perhaps, but still in the same spirit for sure. And I have yet to hear anyone call the earlier film "woke" although I imagine I could find someone to make that argument if I looked hard enough.

And even if we can interpret this interpretation of Fitzwilliam and his journey with a lecture on the evils of imperialism...the miniseries would be in good company. Tolkien was a proper Englishman, but he didn't care all that much for the idea of a global empire ruled by a figurehead monarch and a heavily Protestant parliament. This sentiment is quite clearly expressed in his letters, notably 53 (“I love England, not Great Britain and certainly not the British Commonwealth, grr!”) and 100 (“…as I know nothing about British or American imperialism in the Far East that does not fill me with regret and disgust, I am afraid that I am not supported by even a glimmer of patriotism in this remaining war…”); in some of his public appearances; and in his legendarium, where those who set out to create empires for their own selfish reasons, for power and wealth rather than to serve others and fight against evil, all meet various levels of disaster. Some examples would include:

The Feanorian Elves, who go to war against Morgoth not only to avenge Morgoth's theft of the Silmarils but also to set up their own kingdoms in Middle-earth where they are the most glorious and powerful and need not bow to the Valar, and almost the entire branch of that family dies.

The later Numenoreans after their intervention in the War of Sauron and the Elves keep coming to Middle-earth not to teach and comfort the men of Middle-earth, but to extract tribute and wealth from Middle-earth and to go to war just for the fun of it. This leads directly to the apostasy of Numenor thanks to Sauron and, as a direct result, its utter destruction.

During the reign of Hyarmendacil I, the Kingdom of Gondor reaches the height of its power and glory, and children play with precious stones as though they were marbles. But Gondor forgets its duty to watch Mordor and to protect the west, and until the reign of Elessar the kingdom goes into almost terminal decline.

Even Galadriel is not immune to this; first setting out for Middle-earth out of a lust for power and dreams of empire, this darker side of her nature is one that she has to struggle with almost until the very end of her story, when at the end of the Third Age she rejects the temptation of the One Ring and the possibility of absolute power, but in so doing proves that her journey of growth and repentance is complete and that she is worthy to come home.

When the mystery is finally solved, both Luke and Bridget choose to be bold, to “choose not the path of fear but that of faith” as it were, and to strike out on unexpected journeys that they had never anticipated going on when they first met, but in which they are confident that they can find fulfillment, mission and inner peace. To an extent, that’s what I’ve done with this essay, which is not the essay that I was planning to write this week. However, the story that presented itself in this adaptation provided some unexpected and welcome opportunities to talk about themes that are common between it and Tolkien’s world. Which is fitting, since once he had outgrown his initial idea of writing a mythology specifically for England, Tolkien instead chose to write about certain transcendent themes and ideals and values. As he himself put it, “We have come from God, and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error, will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God.” And this doesn’t even have to apply in the case of an epic myth. Even a made-for-TV Agatha Christie adaptation can fill this role, and we are the richer for it.